DESIGNING FOR HOUSING INSECURITY

IDENTIFY

At the start of our project, my co-lead and I immediately knew we had to narrow down our scope since basic needs insecurity is so broad. Although most basic needs issues are intermingled, we knew that narrowing our scope is crucial in order for our design process to be more effective. We also chose to focus on housing insecurity because we had focused on food insecurity in our first year of this project, hoping to touch upon unexplored avenues. Our first step was to have each member conduct independent research, where we explored how other college campuses tackled similar issues and found relevant statistics that informed our current scope.

For example, in the 2018 University of California Undergraduate Experience Survey,

- 141 individuals, out of 7,653 UCSD responses, are homeless during the Fall-Spring academic year

- 6,144 individuals, out of 7,816 UCSD responses, are sharing their housing with another student

- 4,089 individuals, out of 7,813 UCSD responses, live a mile or greater from campus

Despite the number of homeless indivudals being a minority, we understood that housing insecurity, broadly speaking, encompasses a large number of unique situations. The UCSD Basic Needs Insecurity Committee Report defines housing insecurity as "unaffordable housing costs, overcrowding, poor housing quality, couch surfing, and homelessness". The above statistics are relevant to such issues and as such, we're crucial in identifying the social issue for our project.

Other college campuses have also utilized unique methods of combatting basic needs insecurity, such as

- Donation of unused swipes and low rent co-op housing at UCSB

- The Doorway Project, a pilot cafe at the UW where homeless youth can engage with necessary tools and resources

- SDSU's Hunger and Homelessness Week, a week full of events to inform students about resources for food and housing insecurity

Equipped with our initial research, we proceeded into the immerse phase, where we empathized with our stakeholders and uncover insights to better understand our problem space. Moving forward from the progress of last year's project my co-lead wanted to improve on areas where we felt we could have done better. We both agreed that we would like to put more emphasis on collaborating and communicating with our primary stakeholders, housing-insecure students.

IMMERSE

Our biggest challenge in engaging with our stakeholders, particularly housing-insecure students, is the stigma and connotations that are tied to identifying as housing-insecure. With this in mind, we took upon particularly aggressive measures to engage with as many users as possible. However, our other priority was also to extract rich, qualitative information so we also approached our data collection process with co-designing with our beneficiaries in mind. Ultimately, we arranged a focus group modeled meeting where we conduct flipped journey mapping exercies with each of our users.

For the recruitment process, we utilized:

- Strategic placement of flyers

- Posting on social media, particualarly high-traffic Facebook student groups

- Guerilla recruitment, reaching out to people within our own circles and beyond

Flyer designed by fellow team member Samuel Huang

JOURNEY MAPPING

During the meeting, we began with the journey mapping exercise. Normally, the user would speak with a designer who would then illustrate the journey mapping according to the users' descriptions. However, we thought that it would be more appropriate and accurate if the user could map their own journey while the designer observes and discusses with the user, particularly because we wanted the user to illustrate their feelings too. We had each user map out a typical weekday, from the moment they rise till when they sleep, and illustrate any pain points they may have with commute, engaging in daily hygiene, or obtaining food. We'd later conclude the meeting with some discussion using questions that our community partner proposed while serving hot meals to our meeting participants.

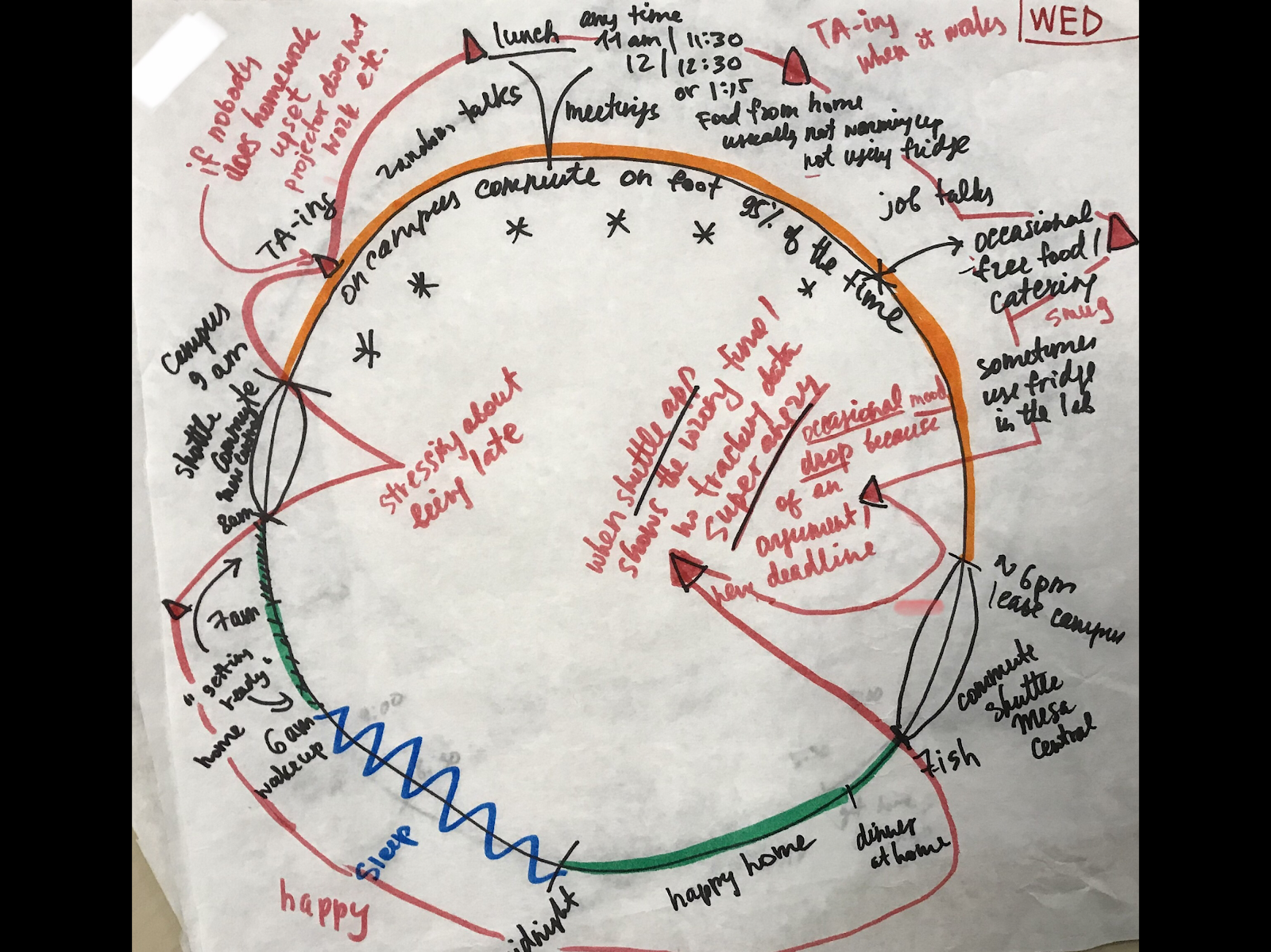

Sample journey map: one circle to illustrate daily happenings and another to demonstrate users' emotions throughout the day

In total, we collected 15 journey maps from 15 students. We had a mixture of undergraduate and graduate students and a diverse set of housing situations: graduate housing, off-campus housing, on-campus housing, and homeless. We categorized them as such since we identified that each type are entitled to different amenities and would have varying experiences.

REFRAME

The most challenging part of this project thus far was this phase. Despite having such a wealth of information, it was very difficult to sort and process this information into insights that could be actionable. We spent several meetings categorizing our journey maps, identifying potential patterns, and making generalizations to help formulate our how can we statements (HCW). In addition, we also consulted with Design For America National Fellow, Irfan Ibrahim, to revise our statements to be more user-centric. Our 3 HCW are:

- HCW give housing-insecure students more accessibility to sleeping spaces?

- HCW bring interacting among transient students more centralized and help them feel integrating into the broader student population?

- HCW help beneficiaries feel less-self-conscious when approaching resources?

IDEATE

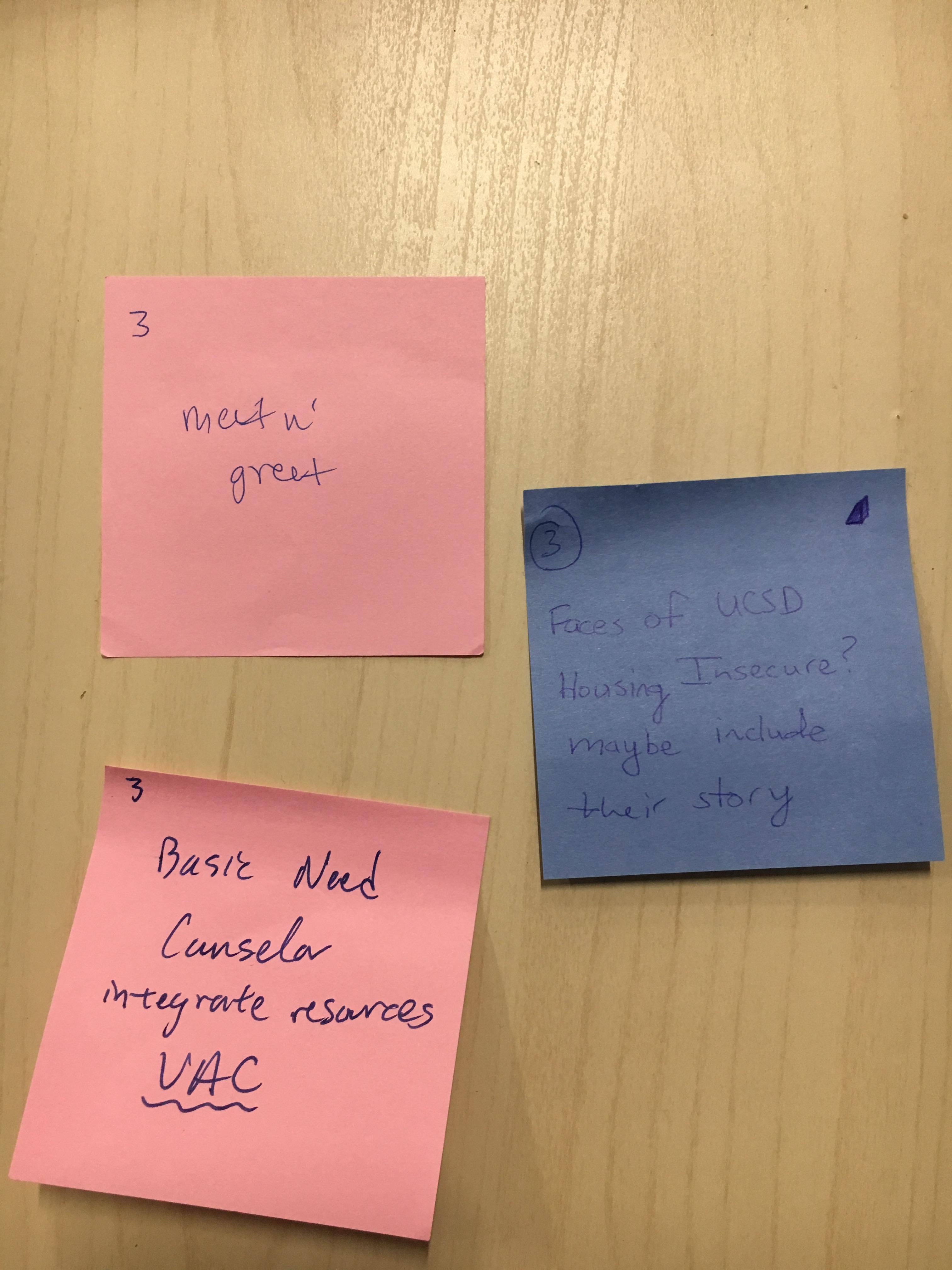

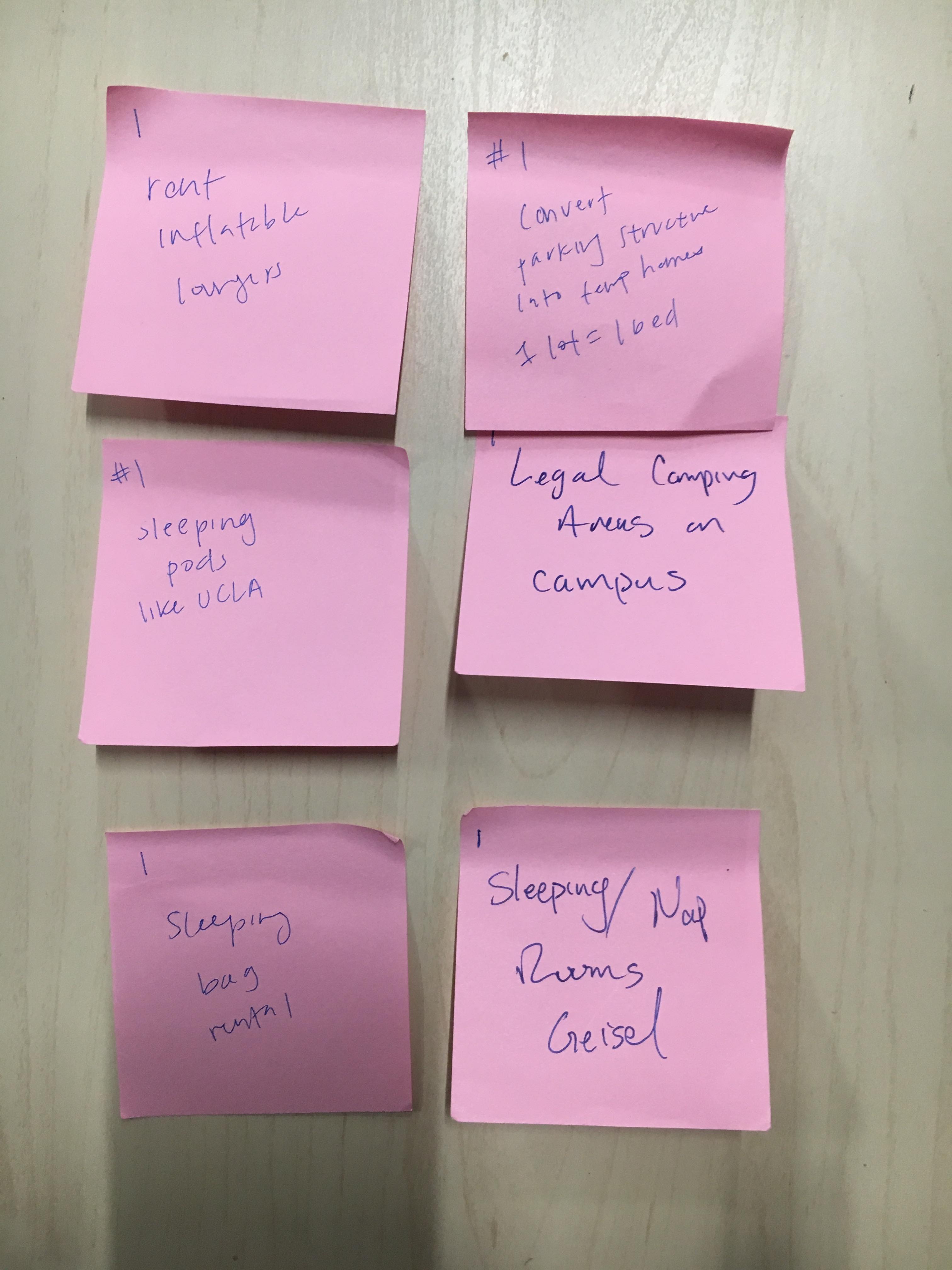

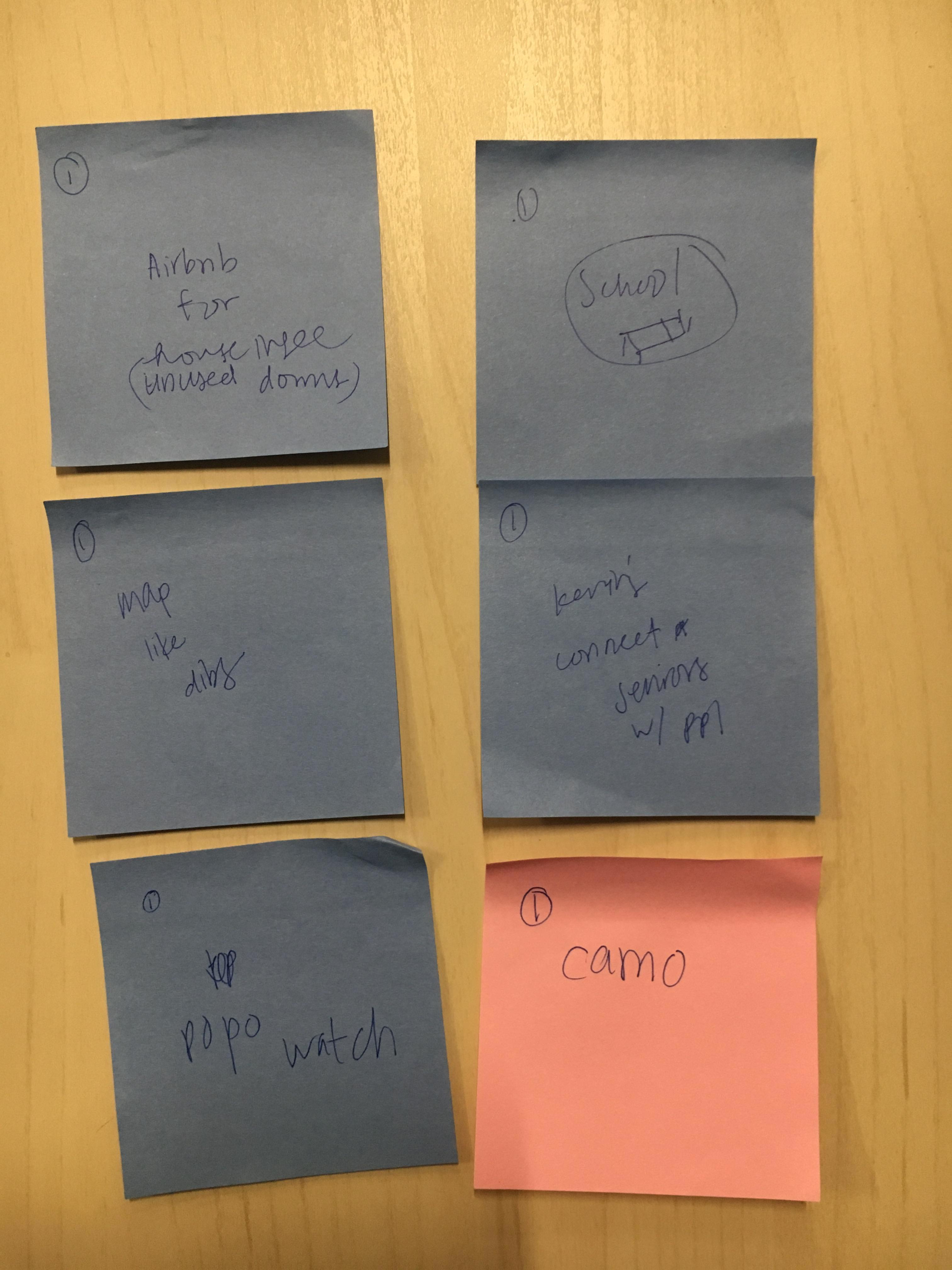

With our three HCW statements, our team practiced an ideation exercise where we simply generated as many as ideas, good or bad, within the span of minute. By the end of exercise, our table was covered in a rainbow of post-its. Afterwards, we use affinity mapping to discuss on what ideas seemed similar, and what we could expand upon for each of the three HCW statements.

These were some of the post-its from our ideation exercise.

We felt that we had a lot of ideas but it was hard to determine their viability and quantifiable measures of success. Per DFA National Fellow Irfan Ibrahim's suggestion, we undertook a prototyping exercise to determine which of the ideas had the best potential to deliver meaningful impact in a short yet significant amount of time.

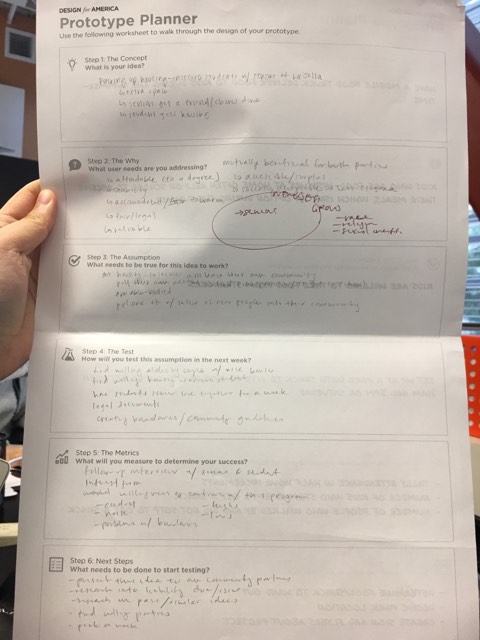

My prototype planner for a senior & student co-housing network.

I was inspired by an interview I saw online where students shared a home with a senior citizen. There seemed to be a naturally symbiotic relationship: the tenant, young and able-bodied, helped with chores and became good friends with the older roommate. The older tenant benefited from a unique friendship that helped curb feelings of isolation. Through this interesting concept, young and old were brought together and many needs were met.

I thought that maybe a similar approach could be used to help housing-insecure students meet their most crucial need, a home. However, as I discussed with Irfan, and my studio lead, Eric Richards, I realized many assumptions were made and a lot of research still needed to be involved.

The biggest concern is attempting to involve seniors as part of the concept. A large part of this concept's viability relied on seniors being willing to open up their homes to strangers and develop a mutual trust in living and sharing a space with people they don't know. That being said, my team and I didnt't heavily focus on seniors during our user research stage mainly because our primary stakeholder are housing-insecure students. We were making a lot of assumptions on a different user group to help our target user group.

This case study will be updated after the project is completed. Come back to hear more soon!